Eating for the First Time: With Medical Complexity

Meet Wendy. A 68 year-old female with past medical history significant for cervical laminectomy, opioid use, COPD, asthma and hypertension. Pt experienced a few days of bloody diarrhea, very poor oral intake, abdominal and back pain, and syncope before being found on the ground by her husband. Wendy was diagnosed with severe ischemic colitis and eventually developed a GI bleed, Tokotsubo cardiomypoathy, cardiogenic septic shock, multi-system organ failure, respiratory failure with intubation, tracheostomy, and PEG tube placement. During her hospital stay she also developed deep-vein thrombosis, fungemia, bacteremia, and klebsiella pneumonia.

When I meet Wendy

Wendy comes to the critical illness recovery hospital on the mechanical ventilator via assist control mode. She is awake, alert, oriented and anxious to get home (like anybody would be). Given Wendy’s medical complexity and recent respiratory failure, I provide an initial evaluation without any intervention. I speak to the respiratory therapist and pulmonologist and it is decided that the patient is a good candidate for aggressive weaning off of the vent. So for now? I use time as a tool and wait for her to progress to a more stable state before providing any aggressive interventions. In the mean time, I provide an ongoing assessment, patient/staff education, and instruction on use of a communication board to communicate basic wants/needs for the next three days until the patient was safely able to come off of the vent. She was identified as stable off of the vent two days after that and her trach was successfully downsized (Shiley #8 cuffed to a #6 cuffless) before a speaking valve was placed.

Time to Eat (Or so I thought)

Given Wendy’s complex medical situation I decide to be conservative and start PO trials with a FEES so I can visualize everything I’m giving her and reduce the risk of silent aspiration which can have a significant impact on the patient’s fragile lungs and high susceptibility to infection. While I detected some wet vocal quality, I was not prepared for the water park I was entering. Secretions were pooling in the valleculae and pyriform sinuses with minimal clearance of ice chips, thin, nectar, and puree trials through the cricopharyngeal segment into the esophagus. With nowhere else to go, significant pooling was visualized in the larynx and trachea on secretions and all consistencies administered. Signs were pointing to extremely reduced base of tongue retraction and posterior pharyngeal wall stripping wave causing severely reduced bolus propulsion. I tried a small amount of ice chips which didn’t make the secretions better or worse, but it was clear that they weren’t going anywhere with any number of effortful swallows or head positioning. On a positive note, the patient did appear to be able to keep her airway clear with persistent coughing and throat clearing. A recommendation for NPO was made and a discussion for ice chips was considered. BUT, before I could consider ice chips I want to get a clear picture of what kind of pneumonia risk we are looking at. So I look back at the chart and review the risk factors of aspiration pneumonia to visualize a risk profile and see if we can manage that risk.

How can I help?

There are clearly a lot of risk factors here. But I’m not going to let that intimidate me. I’m going to focus on what I can manage to see if we can reduce the risk in any way. Many of these risks can and are already being managed effectively. Plus, there is a lot here that I as the SLP have a direct role in improving too. Oral care and secretion management for example. Even though Wendy is unstable, if I can educate the staff on the importance of keeping her mouth clean and train her on secretion management techniques (staying upright and using frequent coughing with effortful swallows) we can improve her ability to protect her airway throughout the day and reduce the amount of microbial-filled saliva sliding into her lungs (nice image, I know).

As noted in the chart, Wendy is refusing PT and OT. Not good. With daily exercises she would improve her potential to become mobile and improve her strength, as well as her functional abilities. That would make such a huge difference for her independence, quality of life, and could significantly lower her risk of aspiration pneumonia. Maybe by educating Wendy on the benefits of physical exercises, she could change her mind. I recommend a psych consult and a meeting with her and the IDT to discuss her goals and how we can help her meet them.

Moving forward

I review the chart review and risk factors one more time before considering my recommendations for PO intake at this time. I think I have an idea of what direction I want to take, but I need to finish one final step first. The most important step actually. I talk to the patient to get a sense of her wants, needs, and expectations based on the risks and benefits at hand. From this conversation I discover that her main concern is her dry mouth and complaints of thirst. She has little desire to eat, but is eager to begin drinking. Anything. Just to tide her over for a little while.

With that information, I assess the whole picture. Given her medical complexity, unstable status, number of risk factors, and severity of dysphagia, the best bet is to keep her strict NPO. But given her craving for something to drink I discuss with her the possibility of providing small amounts of ice chips (no more than 1 oz 3x/day) provided slowly in the upright position with 1 chip at a time; and with direct supervision and close monitoring of vitals, imaging, and respiratory status. I explain that, like anything, there is some risk involved with introducing PO at this time. Next, I explain that the risk will be significantly lowered with physical exercise in therapy and that improving her strength may get her drinking other liquids sooner. With this information, she accepts the current risks and seems open to discussing options with the IDT for an exercise program. She also explains that she truly wants to do therapy, but she’s just in so much pain. With that information a negotiation is made- an agreement to participate with therapy if and when a suitable pain medication is administered.

How did she do?

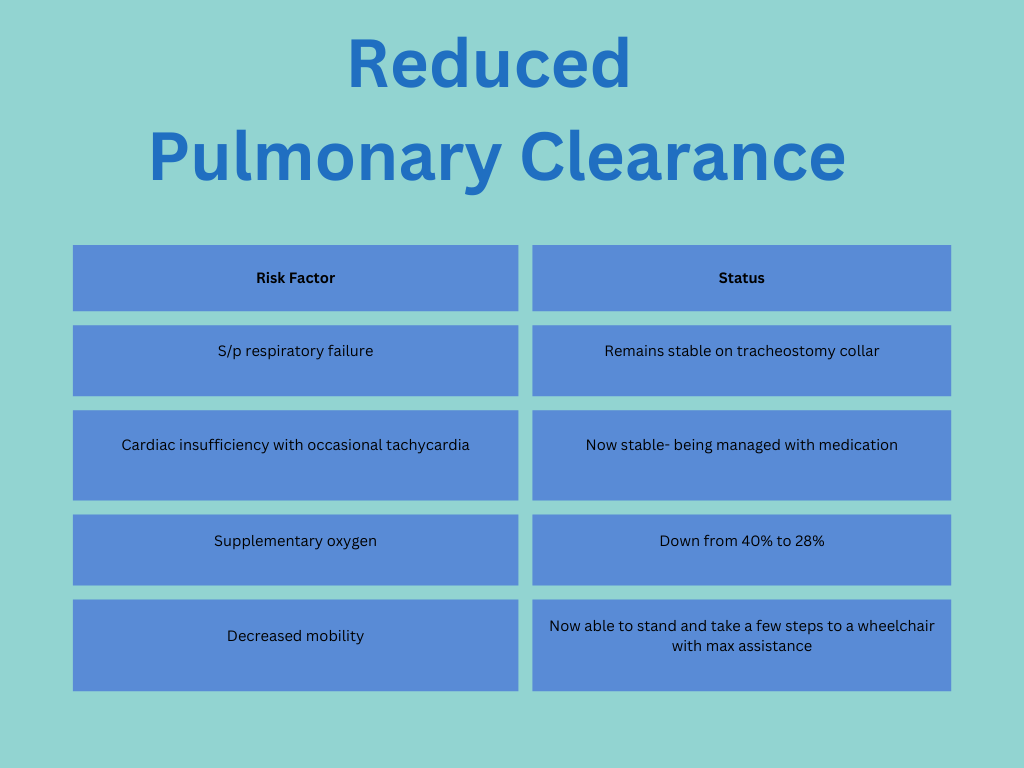

After 12 days, Wendy got more and more involved in therapy and the team continued to manage her condition to the point of stability. The stronger and healthier she became, the more she wanted to get involved in therapy and try new things to improve her functionality. It was an upwards spiral and incredible to see. One by one the risk factors on our chart fell off and we were left with the following:

Wendy has come a long way. She appears to be tolerating the ice chips with less coughing and wet vocal quality and has been completing effortful swallows every day with increased frequency (now up to 100 repetitions a day with ice chips and without ice chips when managing secretions). It’s time to repeat the FEES study. What did it show? Significant improvement. Notable progress has been made in her secretion tolerance, base of tongue retraction, posterior pharyngeal wall stripping wave, and cricopharyngeal segment opening. While residue is still observed. It was only moderate in nature with infrequent pooling into the airway. The few episodes of laryngeal penetration that did occur were cleared out immediately by the patient’s productive cough. No aspiration.

A few weeks later, the patient was finally discharged from our facility on a mechanical soft diet with thin liquids and continued to get stronger and more independent every day. Her appetite had improved and was only receiving occasional bolus feeds through the feeding tube. When I came in to see her one last time she was drinking iced tea, her favorite. She looked up at me and asked for some ice chips. I laughed and told her she graduated and could have whatever she wanted. Why Ice chips? “For old time’s sake. I still remember how they quenched by thirst after not having anything to eat or drink for over a month.” Nothing else needed to be said. I happily obliged.

Liked this? Why not share it?

Leave a comment. I feed on feedback.