My Patient is Aspirating. What do I do now?

What do you do when you have someone who is clearly aspirating and clearly at risk for aspiration pneumonia but doesn't want to hear your recommendations for a modified diet? Do you push what you think is the safest option? Do you allow him to continue down a risky path without persuading him otherwise? How much and what kind of education is essential in these situations?

84-year-old Jacob comes into the hospital after an acute CVA. This is his third one in the last five years. He's very aware of this process and already knows his goals, expectations, and values. But… He's aspirating. A lot. You do a swallow study and observe gross amounts of aspiration on thin liquids. After a tense discussion with the radiologist, you persuade her to keep the study going so you can test some strategies. A supraglottic swallow helps but doesn't remove the bolus from the airway altogether. Time to bring this information to Jacob...

"Hi Jacob, we have today's swallow study results."

"Yeah, I'm aspirating, right?"

"Yes. It's concerning. It's a large amount of aspiration occurring on thin liquids. You have a strong cough but couldn't eliminate all of the aspiration. We are worried about you developing aspiration pneumonia."

"I know, I know. I've been through this before. I'm not interested in drinking the thick stuff, so tell me where I need to sign my life away."

"No, no. We don't do diet waivers here. Instead, I'd like to discuss the costs and benefits and help you make the best choice.

"That's great, but I really don't need to discuss this further. I already decided this after my first stroke when they told me I was aspirating. I realize it's getting worse, but my decision stands. I want to continue eating and drinking the things I love. I only have a little more time left here and want to make the most of it."

Aspiration pneumonia is serious. It tends to affect older adults and those who are medically compromised in more significant numbers and has a mortality of 21%. Further, Jacob may be at an increased risk as 33% of all patients with CVA, whether they are observed to be aspirating or not, may develop a pulmonary infection. In other words, the stakes are high. One thing he does have going for him is a strong cough which may help, but won't completely eliminate the risk of aspiration pneumonia.

This information doesn't change Jacob's mind. He knows what he wants. Patient-centered care would dictate that we support Jacob in this choice and try to reduce the risk as much as we can while moving towards his goal of a regular diet and a safe discharge back home.

We educate Jacob further on what we can and can't control and give some recommendations to improve his prognosis. He's been educated on using a supraglottic swallow to protect his airway and on more general safe swallow strategies to enhance his safety (i.e., sitting upright, drinking slowly, taking small sips, etc.). We talk to him about staying mobile, living a healthy lifestyle, and maintaining an effective oral care routine.

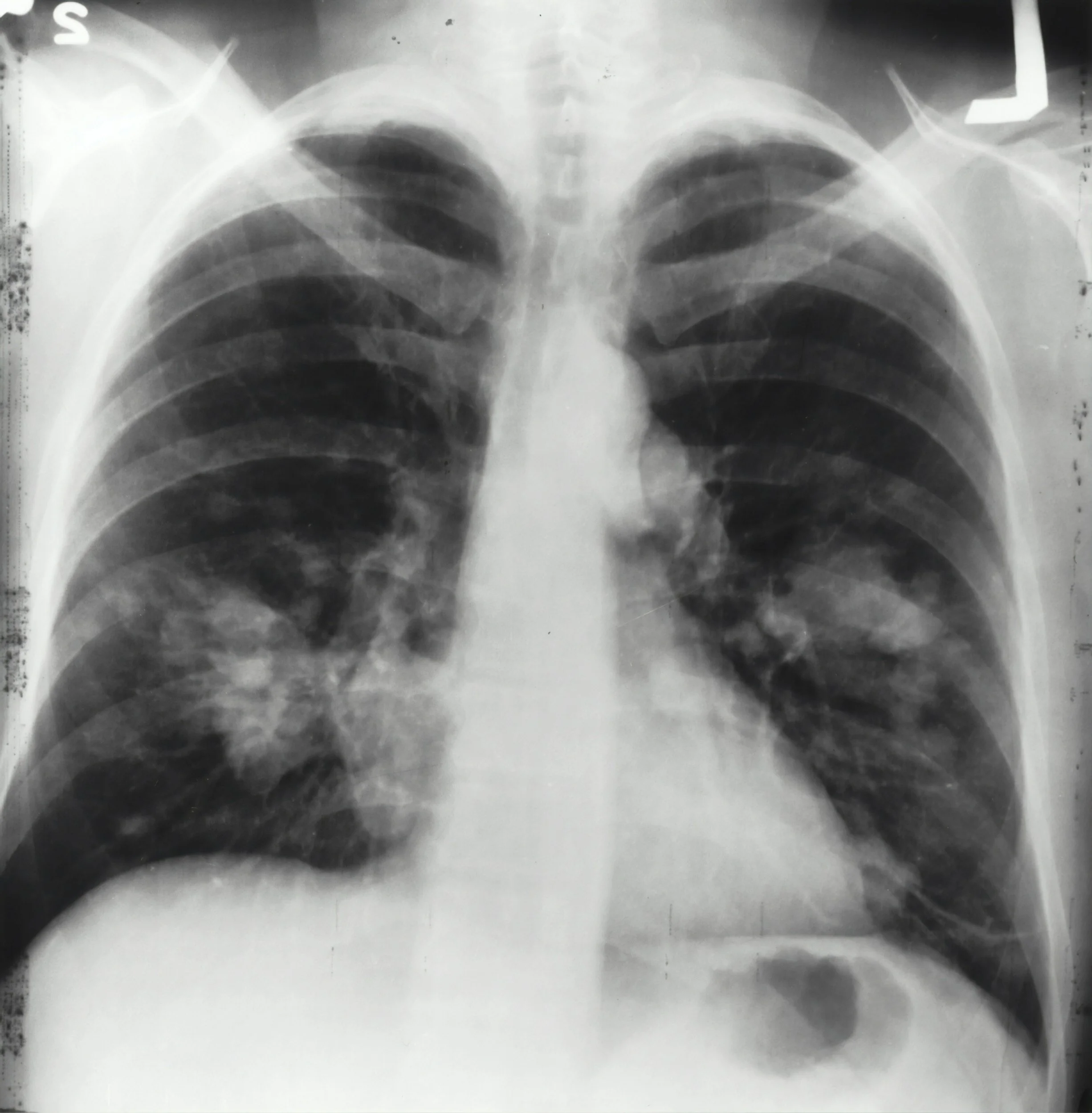

We also examine him closely during his hospital stay to look for signs that an infection might be developing. This way, the team can start treatment for pneumonia as soon as possible, and we can talk to Jacob again about changing the diet consistency if he's open to it. But what signs of infection should we be looking for? And how long after aspiration does an infection usually occur?

Check out this recent blog post on where aspiration goes once introduced into the airway, which details how the lungs respond to aspiration, the types of consistencies we should be concerned about, and what we can do to help.

Aspiration-related symptoms could develop immediately after the event to a few days later. Immediate symptoms may include difficulty breathing and wheezing, which is more likely to occur for solid boluses or large-volume aspiration. The symptoms that develop 24-48 hours after an aspiration event are usually related to pneumonia or associated respiratory conditions and may include dyspnea, increased work of breathing, tachypnea, chest pain, and congestion.

So, suppose Jacob is aspirating for a couple of weeks without developing these symptoms. In that case, he is, at least currently, safely aspirating without adverse reactions. This could change, but it's a good indicator that he may continue to do well and that the benefits may outweigh the risks of resuming his current diet.

Conclusion

Understanding the statistics behind the critical factors surrounding aspiration and aspiration pneumonia is essential to providing adequate education and support for patients with dysphagia. Jacob may know what he wants but is still vulnerable and at a high risk. Our job is to educate and support him towards lowering that risk in a way that fits into the framework of his goals and wishes. The education we provide could make the difference between a patient stuck in a situation they never wanted to be in and having the opportunity to safely pursue their goals. If you ask me which is better, I'll always opt for the latter.

Enjoy learning about clinical decision making? Consider taking our short course, Complex Decision-Making in Dysphagia Management to learn more.